Advances in the Care of Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse

In May 2017, Matthew D. Barber, MD, MHS, was named the chair of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Fellowship-trained in urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Duke, Barber is nationally recognized for his work as a researcher and surgeon specializing in the surgical treatment of gynecologic conditions, particularly urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Question: What are some changes you've seen in the way pelvic organ prolapse is approached in your more than 15 years in the field?

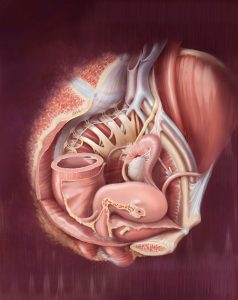

Barber: This is a young specialty—we’ve been taking care of women with prolapse for centuries, but, as a subspecialty of obstetrics/gynecology, it’s only been around for 15 to 20 years—so there have been a lot of changes as we try to understand the condition and how to better care for women with it. First, we have a much better idea of the relationship between the anatomy of a woman’s pelvic organ support and the symptoms that she develops. There has also been a large attempt to improve the outcomes of surgical repairs. From my perspective, though, one of the most important changes is that the care of women with this condition has become much more patient-centered.

Question: Are there any common misconceptions about pelvic organ prolapse?

Barber: There’s a huge misconception that any loss of support of the pelvic organs should be considered a disease, and, in the past, I think we had a lot of overtreatment. Some change is normal, particularly after vaginal delivery; that, in and of itself, shouldn’t be considered a disease. This condition is really about quality of life, so it’s critical that any decisions about treatment be made with the patient, based on the symptoms she’s having and how much they're bothering her, especially before we consider something like surgery. Fortunately, women with symptoms have a spectrum of options, ranging from simple pelvic muscle exercises to vaginal inserts (ie, pessaries) to surgery.

Question: Where do you see the field of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery going?

Barber: I think we will see advances in the surgical treatment of the disease. I’m particularly hopeful around bioengineering to develop tissue scaffolds that can be used instead of synthetic meshes to augment the surgical repair procedures that we already have. There’s also some interesting work being done in animal models on stem cells and stem-cell homing that may translate to patient care, which could be very exciting.

We’re also working to better understand which women are at a higher risk of developing more serious prolapse so that we can target prevention strategies. There are a lot of interesting new data on the factors that predispose women to developing these conditions. Prediction calculators that allow an individual woman to understand her risk of developing prolapse or a related condition are right around the corner. If we were able to identify women at high risk early enough in life—ideally before childbearing—then we might be able to help prevent the condition, for example by considering cesarean delivery in certain patients or counseling patients on lifestyle changes to decrease their long-term risk.

It’s a chronic condition, and our surgical treatments are not perfect—they come with risk—so, if we can prevent people from getting it in the first place, women will be better off.