ALS Trials Redesigned With Patient-Centric Approach

Although dozens of clinical trials for amyotropic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been conducted, none have identified an effective, disease-modifying therapy. Duke neurologist Richard Bedlack, MD, PhD, hopes to change that with Replication of ALS Reversals (ROAR), a program that uses a widely inclusive, patient-centric approach to testing alternative therapies that have been correlated with an ALS reversal in at least 1 person.

The program’s first ALS trial, testing whether the commercially available soy peptide lunasin can decrease the rate of disease progression, completed enrollment in record time, averaging 9.1 participants per month compared with the ALS trial average of 2. The trial’s high enrollment rate is likely the result of its few barriers to enrollment, Bedlack explains: The trial has few inclusion criteria, and only 3 visits to Duke are required during the yearlong study.

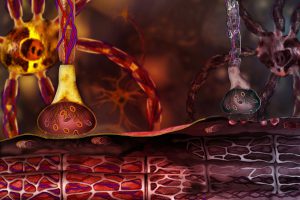

In addition, the study spurred excitement among potential participants because, unlike previous trials, which have been based on studies in cell culture or animal models, the lunasin trial was modeled after the regimen of a patient with ALS who experienced a real reversal of the disease. The study is also one of the few to measure a biomarker—in this case, histone acetylation patterns, which are abnormal in patients with ALS but may be modified by lunasin.

“In most previous trials, we didn’t select patients for a certain pathophysiology or measure anything in the brain or cerebrospinal fluid, for example,” Bedlack says. “Without a biomarker, we have no way of knowing why dozens of previous ALS trials failed. Maybe the dose wasn’t high enough. Maybe we used the wrong route of administration.”

One particularly unique aspect of Bedlack’s approach is that he posts the trial’s Institutional Review Board–approved protocol as well as interim results on the website PatientsLikeMe, so that people with ALS who are not participating in the trial can still try the trial’s treatment regimen. Bedlack hopes this approach will help patients with ALS avoid the many alternative therapies available online that are likely to be costly, ineffective, and potentially physically harmful.

“By making our protocol publically available,” he says, “we’re trying to say, ‘We understand this community wants some ideas on what they can self-experiment with, so here’s something that appears to be well tolerated and safe, with a plausible mechanism, that someone with ALS tried and then appeared to get better.’” He adds that all the products that will be tested in the ROAR program are available over the counter.

Although it is too soon to determine whether lunasin can slow disease progression, the trial has already been successful in several ways that suggest the study design will be appropriate for future ROAR program trials, Bedlack notes. In addition to the unprecedented enrollment rate, the rates of self-reported adherence and compliance at 1 month were very high, and participants reported very little perceived burden and few adverse events. Patient-reported measures of the ALS Functional Rating Scale also had strong agreement with those of the study coordinator, providing further evidence that such a study design is feasible for future trials.

“No matter what we learn about lunasin, we’re learning something about a study design that’s never been used before,” Bedlack remarks. “We hope to show the ALS community that there’s another way to do research that can get a lot more people involved.”