Managing Breast Cancer Brain Metastases

A 33-year-old woman was referred to Duke after being diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer. Because the tumor’s hormone receptor expression was very low, hormonal therapy was not indicated, and she was started on chemoradiotherapy.

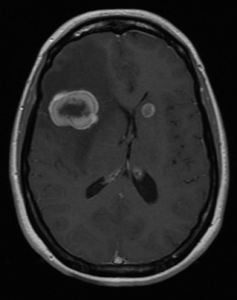

The cancer stayed in remission until she began to have severe headaches 5 years later. She presented to the emergency department at Duke Raleigh Hospital. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed lung metastases, a small liver lesion, and multiple brain metastases, including a large tumor in her right frontal lobe (Figure 1). The brain tumor needed to be resected immediately.

FIGURE 1. Before frontal craniotomy

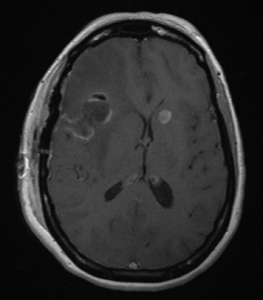

Anna R. Terry, MD, the neurosurgeon on call, quickly coordinated a team of operating room staff to help her perform the surgery. Using Brainlab to help localize the tumor and plan the incision, she resected the tumor. Postoperative MRI showed that the resection had been successful (Figure 2).

“Although the resection itself is pretty straightforward, it takes a lot of teamwork to make it happen safely,” Terry says. “Being able to quickly pull together a team at any time—day or night—is critical to our ability to help patients like this.”

The next morning, the patient had a consultation with a radiation oncologist to plan her treatment course and schedule a follow-up appointment with Paul Kelly Marcom, MD, the medical oncologist who had helped treat her primary breast cancer. She was discharged the next morning.

FIGURE 2. After frontal craniotomy

Two weeks later, she began a course of fractionated radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery to treat the smaller brain tumors. Repeat marker assessment of the brain tumor showed low levels of hormone receptor expression. Marcom started her on treatment with ovarian ablation, an aromatase inhibitor, and a cell-cycle inhibitor.

“This case demonstrates the need for improved treatment options for this type of breast cancer—something the Duke breast program is working on,” Marcom notes. “But the receptor expression change makes trying this combination a reasonable option. We will follow her closely and, if it does not work, move to other treatment options.”

The patient tolerated the treatments well and experienced no serious adverse effects. Now, 3 months later, she’s feeling well, and she’s back to her usual activities.

“Historically, the prognosis for someone with widely metastatic disease that has spread to the brain was often not great,” Terry says. “However, with the broad range of treatment options we have at Duke, I am optimistic she will continue to do well for quite a while.”