Pancreatitis Leads to Serious Complications

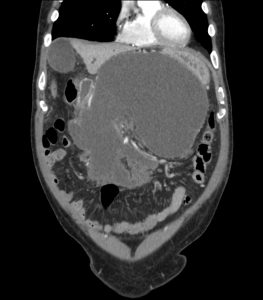

FIGURE 1: 6-week, follow-up CT scan of patient before intervention.

FIGURE 1: 6-week, follow-up CT scan of patient before intervention.

A 66-year-old man was admitted to Duke Raleigh Hospital with pancreatitis, likely of biliary origin. Computed tomography (CT) revealed concern for necrotizing pancreatitis (nearly 100% necrosis), but his clinical course was mild, and his pain soon improved. He was discharged after 12 days with follow up.

However, when he returned to the hospital for follow-up CT 6 weeks later, he had developed severe abdominal pain, weight loss, and early satiety. CT revealed a large peripancreatic fluid collection with a solid component (walled-off pancreatic necrosis) that was compressing his stomach and other intra-abdominal structures (Figure 1). The fluid collection needed to be drained immediately.

Not unexpectedly, draining the fluid led to secondary infection of the remaining necrotic tissue in the pancreas. Without treatment, the infection could be lethal.

Question: What approach was taken to minimize the risk of complications and mortality and reduce hospital stay?

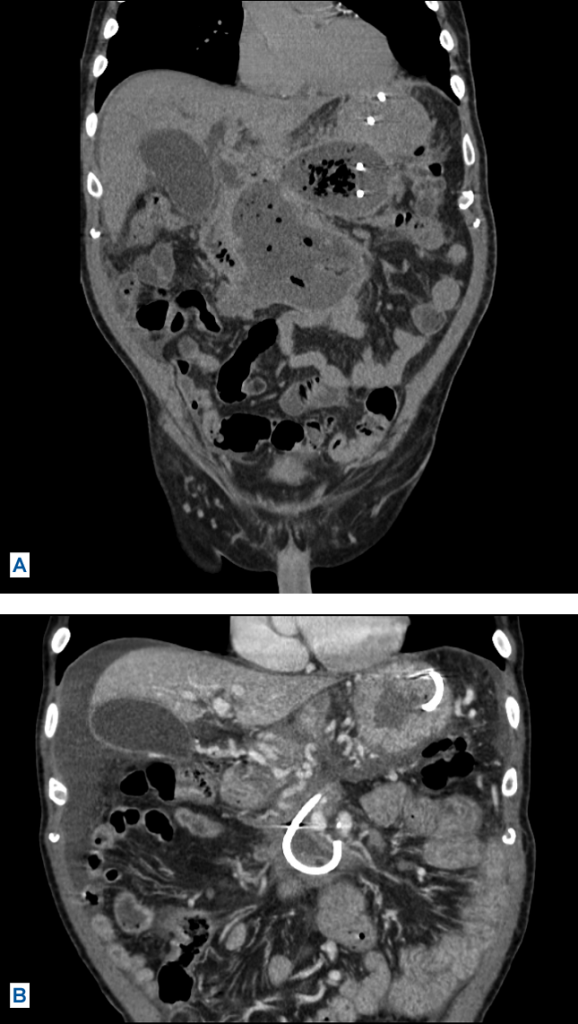

FIGURE 2: (A) CT of patient after several interventions. (B) CT of patient after interventions were completed, showing full resolution of walled-off necrosis.

FIGURE 2: (A) CT of patient after several interventions. (B) CT of patient after interventions were completed, showing full resolution of walled-off necrosis.

Answer: Duke gastroenterologist Jorge Obando, MD, used the “step-up approach” (as proposed by the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group), starting with the most minimally invasive technique available, endoscopic drainage, followed by a series of outpatient endoscopic necrosectomies. Using this approach, Obando and his team successfully controlled the infected necrosis without resorting to more invasive measures such as percutaneous drains or surgery (Figure 2).

Just 15 to 20 years ago, all necrosectomies were performed surgically, Obando explains. Patients would stay in the hospital for months, and mortality rates were often as high as 30%. With the new step-up approach, surgery is performed as a last resort, only after endoscopic and percutaneous drainage fail.

“This was the largest fluid collection many of us had ever seen,” he says. “We knew we would have to put the patient on an intensive endoscopic necrosectomy schedule, and each one of those procedures is quite long and tedious. But the alternative is terrible; we knew we had to dedicate ourselves to taking this approach to give him the best possible chance of a good outcome.”

Obando performed the first drainage with placement of a new stent to facilitate subsequent necrosectomy procedures. Duke gastroenterologists M. Stanley Branch, MD, and Rebecca Burbridge, MD, performed the next 2 necrosectomies before Obando performed 8 more. Critical to achieving a successful outcome was having a team of gastroenterologists who could perform the procedure, especially given the number that ultimately needed to be performed, Obando notes.

The patient was able to return home after each procedure, allowing him to maintain a relatively good quality of life. He also did not experience any complications or pain from the procedures, Obando reports.