Postoperative Complications Following Prostatectomy

A 47-year-old man was referred to a urologist when his annual prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value increased to 14.0 ng/mL. After 1 month of oral antibiotics, his PSA value had increased to 15.4 ng/mL. Transrectal ultrasonographic-guided prostate biopsy revealed high-risk prostate cancer. He was counseled on his options and underwent robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in October 2012.

He was discharged on postoperative day 3, but he experienced difficulty with pain control from the outset. Within days, he developed a fever (102 °F) with painful voiding and severe pelvic pain. The patient also reported “air bubbles” in his urine and yellow fluid draining from his rectum.

Question: What postoperative complication has this patient developed, and what are the most appropriate management options for him?

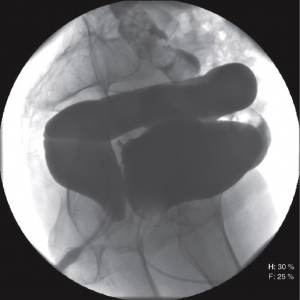

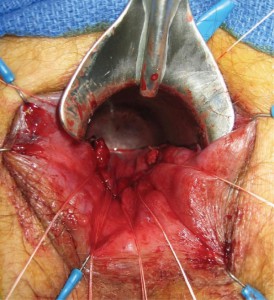

Answer: The patient developed postoperative rectourethral fistula (Figure 1). Although it is challenging, the condition is correctable through advanced reconstructive surgery and a multidisciplinary approach to care.

FIGURE 1. Transanal view of the fistula

Rectourethral fistula is a rare complication of therapy used for prostate cancer. Such complications occur in less than 1% of radical prostatectomy cases.

The patient was stabilized with diverting colostomy to prevent stool from entering the bladder. A Foley catheter was kept in place to divert urine away from the rectum.

The patient met with Aaron Lentz, MD, a physician at Duke Medicine, for repair of the fistula in November 2012, shortly after the colostomy was performed. The patient was referred to Lentz because no doctor in the patient’s home city performed these types of complex fistula repairs.

Lentz is trained in reconstructive urology, a relatively new subspecialty combining elements of plastic surgery, urology, and colorectal surgery. Reconstructive urology can help improve and restore function in select patients as well as improve aesthetics for a patient who has endured injury, cancer, surgical complications, or congenital conditions.

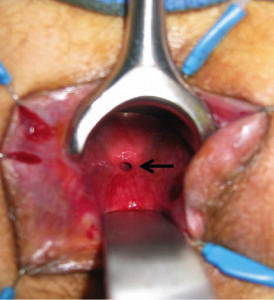

FIGURE 2. York-Mason posterior trans-sphincteric

approach

Although these fistulas are challenging problems, Lentz explains that they can be corrected with the appropriate surgical technique. “The quality of life can be miserable for these patients,” he says. “The goal of reconstructive urology is to restore normal urine flow so patients can regain their quality of life.”

In this case, the tissue was too edematous and friable for an immediate repair. A suprapubic catheter was placed so the urethral catheter could be removed. The suprapubic catheter was more comfortable for the patient and lowered the risk of damage to his urethral sphincter.

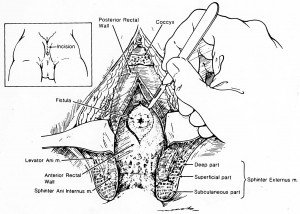

FIGURE 3. Advancement of the rectal

mucosal-submucosal flapstula

In March 2013, Lentz teamed up with colorectal surgeon Linda Farkas, MD, to close the fistula tract with a York-Mason fistula repair (Figure 2). “With the patient lying flat on his stomach, we opened the posterior rectal wall, cored out the fistula tract, and then very carefully reconstructed the urethral tissue and the rectal tissue to prevent the fistula from recurring,” Farkas explains. “Patients then continue with both urinary diversion and a colostomy until the fistula tract has completely healed,” says Lentz.

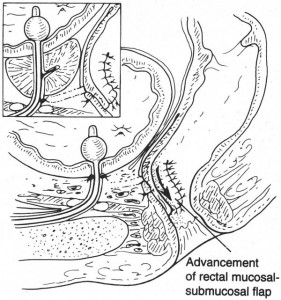

Depending on the size of the fistula and the patient’s history of radiation exposure, the repair sometimes involves use of a gracilis muscle flap, buccal mucosa graft, or both (Figure 3). In this case, Lentz and Farkas mobilized local flaps of healthy tissue to reinforce the repair and separate the rectum from the urethra (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Completed closure with rectal

advancement flap

Colostomy was reversed several months after the fistula repair. The patient required no further treatment for prostate cancer, and he has had no problems with urinary incontinence. His post-prostatectomy erectile dysfunction is managed with oral medications.

“Our goal with the surgery is not only to improve function, but also to improve quality of life. And,” says Lentz, “this patient has pretty much gotten his life back.”

“What I truly love about reconstructive surgery is the uniqueness of each case,” Lentz says. Each case poses a tactical and a surgical challenge, which, he explains, “requires a highly individualized and carefully planned and executed surgical approach to address the problem and underlying anatomical and medical cause.”