Sarcoma Treatment Calls for Intricate Teamwork

A 37-year-old American woman who served in a community in Senegal with her husband and children was having unusual leg and knee pain. She attributed the pain to previous injuries until she needed relief and visited a doctor. Radiographs were obtained in Senegal and revealed a growth in her right proximal tibia.

Upon her return to North Carolina in February 2014, she was immediately seen by sarcoma specialists at Duke and another round of x-rays was obtained. Radiologists found a mass on the x-rays concerning for cancer as well as a fracture of the knee joint. Biopsy was performed within 24 hours of her arrival at Duke and revealed cells consistent with a small, round, blue cell tumor. Lymphoma was ruled out.

Question: What was the patient's diagnosis, and what treatment options were offered to her?

Ewing sarcoma is a relatively rare tumor most often seen in the extremities of children. No metastases were present. The patient’s age and the position of her tumor at the knee made her treatment challenging.

Forty years ago, the treatment of choice for Ewing sarcoma was amputation, and many patients died of metastatic cancer. Over the years, treatment has improved and now involves induction chemotherapy (≤ 5 agents) to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery and consolidation chemotherapy; radiation may also be necessary.

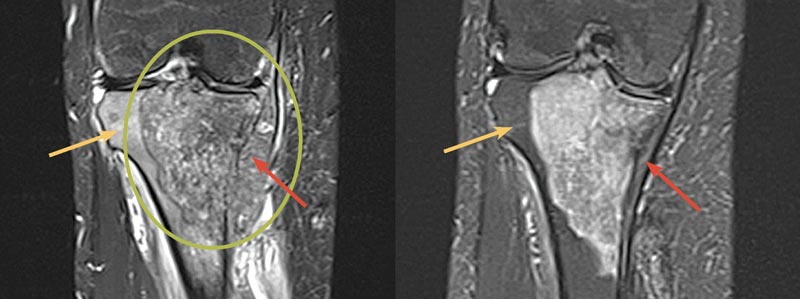

At the time of her first appointment, the mass in the proximal tibia measured 7.9 × 7.2 × 5.6 cm (Figure 1, left), so the patient began 3 months of multiagent induction chemotherapy. This regimen consisted of alternating cycles of vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide with ifosfamide and etoposide, administered before surgery.

FIGURE 1. Left: Initial MRI of the patient’s right proximal tibia mass (green circle) with a soft-tissue component (red arrow) and marrow edema (yellow arrow). Right: MRI of the patient’s right proximal tibia after induction chemotherapy showing a marked decrease in the size of the soft-tissue component (red arrow) with decreased marrow edema (yellow arrow). MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

Induction chemotherapy resulted in a marked interval decrease in the size of the soft-tissue component of her disease and a decrease in marrow edema. Imaging revealed evidence of this response, with the tumor shrinking to 8.0 × 5.5 × 4.9 cm (Figure 1, right).

After discussing surgical alternatives (including possible amputation), limb-salvage surgery was performed by removing the tumor and reconstructing the defect (Figure 2). Brian Brigman, MD, PhD, an orthopaedic oncologist and director of the Duke Sarcoma Program, conducted the resection, which involved removing part of the proximal tibia and replacing it with an artificial knee as well as providing coverage with a muscle flap and skin graft.

FIGURE 2. Postoperative x-ray of the patient’s leg

The pathologic fracture in the patient’s knee joint caused added concern about potential contamination with microscopic tumor cells because the surgery didn’t resect the entire knee. Thus, radiation was also used.

“This patient was a candidate for radiotherapy, which we routinely suggest for a higher-grade tumor or if the tumor is larger than average,” explains Nicole Larrier, MD, a pediatric radiation oncologist who treated the patient’s tumor.

After surgery and radiotherapy, the patient resumed chemotherapy to complete a total of 17 chemotherapy cycles during a 1-year period. The patient began exercises that gradually bent her knee more fully, and, within a few weeks, she could walk without a walker or other form of assistance.

To date, she has no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient will follow up quarterly after chemotherapy for evaluation, with attention to her leg and lungs, Brigman says.

Referring Suspected Cases

Patients often become aware of sarcomas after seeking treatment for incidental injury or pain that they attribute to other activities, such as exercise. Pain due to sarcoma does not typically improve with time, and patients may have significant swelling.

Any tumor larger than 5 cm that is deep in the fascia is worth referring to a sarcoma center, Brigman says. If a rapidly growing mass is observed, then imaging should be promptly obtained, and, if findings raise concerns, then referral to a sarcoma service is warranted.

“One thing that cannot be overemphasized is the fact that, if there is any suspicion of sarcoma whatsoever, patients are best served in centers with multidisciplinary expertise,” says oncologist and sarcoma specialist Richard Riedel, MD.

Duke takes a multidisciplinary approach to each patient’s case, and experts see patients on the same day, Brigman says. At a minimum, experts in surgical oncology, medical oncology, radiology, radiation oncology, and pathology meet regularly to discuss sarcoma cases.

New technology is also available to enhance sarcoma care. For example, Duke uses navigation-assisted sarcoma resections for pelvic tumors and portable computed tomographic scanners for intraoperative imaging. Duke also has open drug, radiotherapy, and surgical trials for other alternatives to sarcoma treatment.