Treating Recurrent Melanoma

After presenting to her local dermatologist with an irregular mole on her left upper back, a 54-year-old woman was diagnosed with malignant melanoma and referred to the Duke Cancer Center. Although ulceration was not observed, the 0.51-mm thick melanoma had a mitotic rate of 4 mitoses/mm², leading it to be classified as stage T1b melanoma.

Concerned that the tumor was exhibiting aggressive tumor biology, surgical oncologist Paul Mosca, MD, PhD, recommended wide excision and opted to perform sentinel node biopsy. The patient had previously undergone left modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer that included removing all the lymph nodes on her left side; therefore, the melanoma on the left side of her back mapped to sentinel lymph nodes in the right axilla, so Mosca performed right axillary lymph node biopsy.

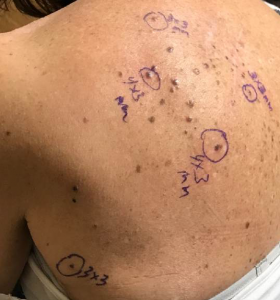

FIGURE 1. Pigmented lesions on the patient's upper back

The surgical margins and sentinel lymph node were negative. However, the wide excision revealed microsatellites, converting the melanoma to stage IIIC (T1b N2c) melanoma. Computed tomography performed to evaluate for distant metastasis was negative.

Months later, she developed multiple pigmented lesions on her left upper back in the region of the prior excision site for melanoma (Figure 1). Biopsy confirmed the presence of recurrent melanoma. Initially, the lesions were localized and could be excised, but soon they increased in number, such that she was no longer a candidate for surgery.

Question: What were the patient’s treatment options, and how was she successfully treated?

Answer: The patient was offered systemic immunotherapy with a programmed death 1 inhibitor or treatment with the new oncolytic virus therapy talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC). She was successfully treated with T-VEC, achieving complete pathologic response.

Although T-VEC—a genetically modified herpesvirus preparation directly injected into tumor deposits—has an overall projected response rate of 25%, Mosca says he and his team suggested it as a possibility because evidence suggests the rate of response may be higher for very small lesions. The patient elected to try the new therapy, he says, because it is generally well tolerated and has low toxicity compared with systemic immunotherapy.

“Identifying the optimal evaluation and treatment plan can be very tricky,” Mosca explains, “so it is critical that we not only have the entire spectrum of options, from the most basic diagnostic and treatment approaches to more complex adjunctive services, but that we also deliver care via a talented, collaborative, multidisciplinary team.”

FIGURE 2. Sites of punch biopsies

To begin treatment, Mosca administered an initial low-dose injection of T-VEC, followed by a higher second dose 3 weeks later. The patient continued to receive injections every 2 weeks for a 4-month period.

Slowly, although their appearance remained unchanged, the lesions began to flatten. The results of punch biopsies performed at the end of the treatment were negative, indicating complete pathologic response (Figure 2). Findings on repeat imaging were negative, suggesting that there was no evidence of any tumor present in her body.

“This is essentially the best possible outcome for her—at least in the near term,” Mosca concludes. “She was able to come to the clinic once every couple of weeks for simple injections with minimal side effects rather than needing any systemic therapy with potentially severe toxicities, and now she’s in complete remission.”