Unusual Anatomy of the Nasolacrimal Duct

A 3-month-old infant was referred to a local pediatric ophthalmologist for constant tearing and mattering of her lashes, with recurrent infections of the nasolacrimal sac that required an episode of intravenous antibiotics. Following unsuccessful surgery to open the tear-drainage system, the patient was referred for further evaluation and care to Duke pediatric ophthalmologist Laura Enyedi, MD.

Enyedi observed that the patient had bilateral dacryocystoceles with a risk of intranasal cysts that often occur in conjunction with dacryocystocele, so she scheduled a joint surgical procedure with pediatric otolaryngologist Eileen Raynor, MD, to perform simultaneous nasolacrimal duct probing with nasal endoscopy and removal of the nasal cyst.

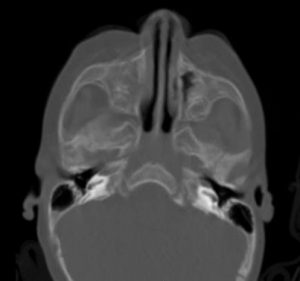

During the procedure, Enyedi and Raynor encountered an unusual, dense, bony blockage of the nasolacrimal system. Computed tomography confirmed that the infant’s nasolacrimal ducts “dead-ended” into the maxilla, leading to a backup of fluid that provided the ideal environment for infection.

Question: What procedure did Raynor and Enyedi perform to clear the obstruction?

FIGURE 1. Computed tomography after dacryocystorhinostomy

FIGURE 1. Computed tomography after dacryocystorhinostomy

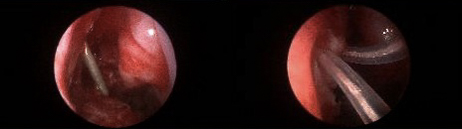

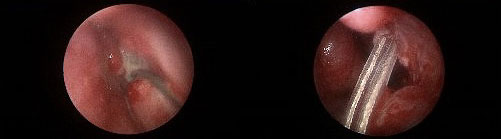

Answer: Raynor and Enyedi performed endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy to create a new opening for the nasolacrimal duct and placed a silicone stent to prevent scarring (Figures 1-3). Almost immediately, her recurrent infections stopped.

Raynor notes that this case was highly unusual. “You will sometimes see some blockage due to a little cyst or something like that,” she says. “But I’ve never seen a case where the nasolacrimal ducts don’t form at the end on both sides or at such a young age.” Enyedi agrees: “I have performed hundreds of these procedures and have never encountered another situation in which the duct was so malformed.”

FIGURE 2. Right lacrimal duct opening before (left) and after (right) dacryocystorhinostomy

FIGURE 3. Left lacrimal duct opening before (left) and after (right) dacryocystorhinostomy

FIGURE 3. Left lacrimal duct opening before (left) and after (right) dacryocystorhinostomy

To modify the procedure for an infant, Raynor and Enyedi used small instrumentation and employed Brainlab (Munich, Germany)—an optical tracking system—which allowed them to confirm their location in the patient’s nose as they performed the surgery. The Brainlab system dramatically improved the team’s ability to visualize and repair the problem, Enyedi says.

After examining the patient during an office visit to remove the stents, Enyedi reports that the child is thriving and has had no further infections or abnormal tearing. “Her eyes and visual system are developing beautifully, and her tear drainage system is functioning normally,” she says. “I do not expect her to have any further problems.”

Having both ophthalmology and otolaryngology specialists with extensive experience in pediatric cases provide their different perspectives on the same problem, Enyedi and Raynor agree, enabled Duke to offer a great solution for a challenging case.