Vision Loss Due to Herniation of the Optic Chiasm

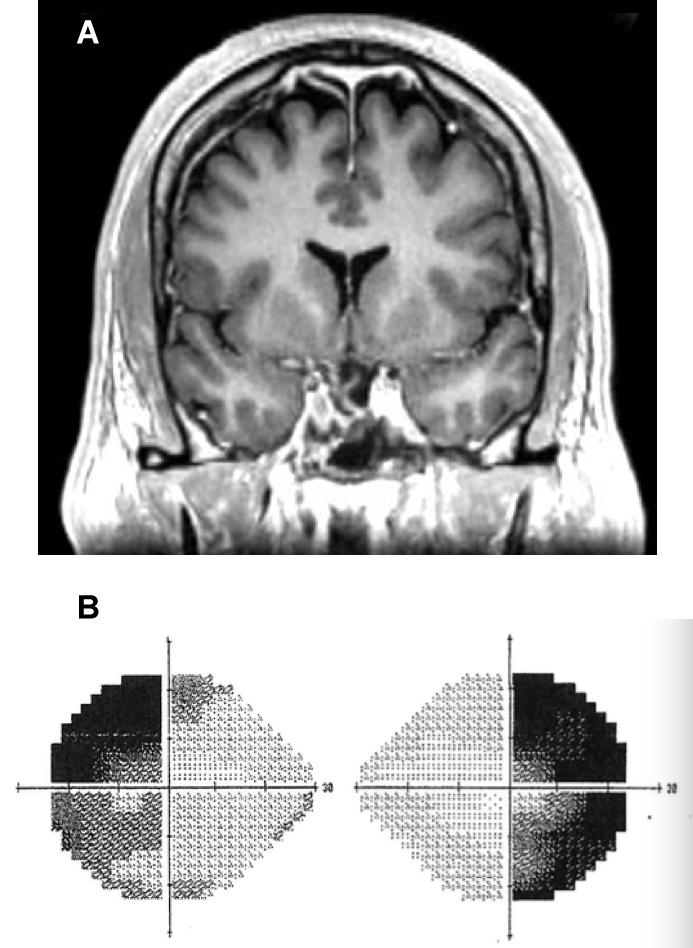

FIGURE 1: A) MRI revealing herniation of optic chiasm; B) Patient’s visual field

After reporting bitemporal hemianopsia, a 48-year-old man was diagnosed with a large prolactinoma. Although the tumor was successfully treated with cabergoline, 5 years later, the patient noticed his vision once again starting to collapse, suggesting that the tumor had returned and was no longer controllable with medication. The patient contacted the multidisciplinary pituitary tumor clinic at Duke.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at Duke failed to reveal the presence of a pituitary tumor recurrence. Rather, in the absence of the prolactinoma, the optic chiasm had herniated into the pituitary sella, causing traction on the optic apparatus, resulting in progressive loss of his peripheral vision (Figure 1).

Question: How was the patient’s vision restored without disturbing the delicate structures around his pituitary?

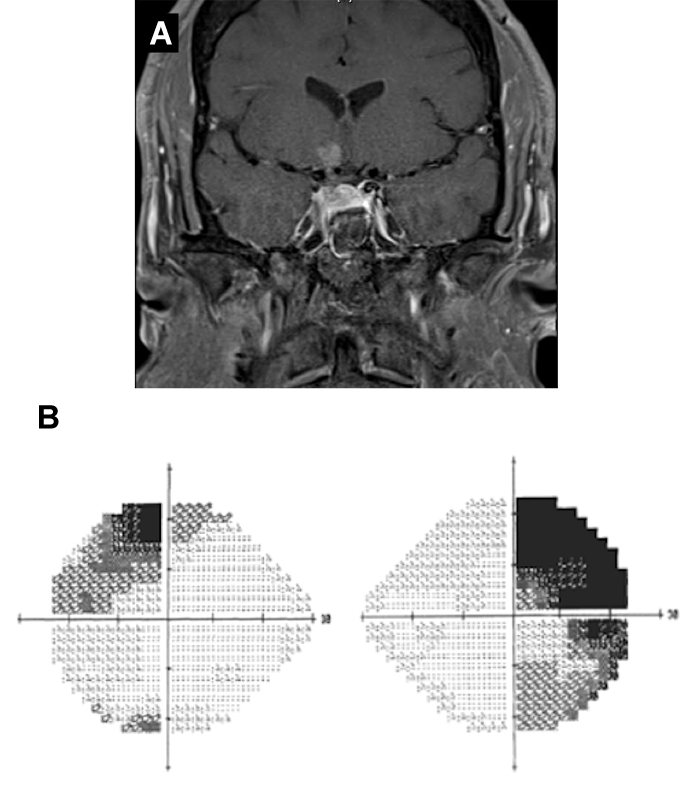

FIGURE 2: A) MRI demonstrating that optic chiasm has been elevated; B) Patient’s visual field following surgery

Answer: Using an endoscopic approach, neurosurgeon Patrick Codd, MD, and endoscopic sinus and skull base surgeon David Jang, MD, propped up the diaphragma sellae with a collagen-based material, thereby elevating the optic chiasm and releasing the pressure on the optic nerve. The patient regained much of his peripheral vision within 6 months, without affecting the hormone function of his pituitary (Figure 2).

The location of the optic chiasm makes it risky to manipulate, explains Patrick Codd, MD, who specializes in endoscopic and minimally invasive neurosurgical techniques. On the one hand, using an endoscopic approach to elevate the optic chiasm directly risks injury to the pituitary, which would cause significant harm to the endocrine system. On the other hand, using a supraorbital keyhole approach risks injury to the delicate structures in the brain.

Ultimately, Codd and Jang decided that the best method would be to use an endoscopic approach to elevate the entire dura lining the sella turcica. The plan would be for Jang, an expert in nasal anatomy and endoscopy, to help Codd access the sellae, in order to perform the chiasm elevation under direct endoscopic guidance without violating the dura.

The next challenge was identifying an appropriate material to elevate the sellar dura. The team discussed several artificial materials before Jang proposed the idea of using a collagen-based biomaterial. The benefit of using such a substance, Jang explains, is that, unlike other materials, biomaterials can integrate into the surrounding tissue and the mucosa can grow over it.

To minimize the risk of injury to the optic nerve during surgery, Codd and Jang enlisted the aid of a neuromonitoring team to enable them to visualize the patient’s optic nerve and visual cortex and monitor changes in vision.

The surgery went smoothly, and the patient was discharged the next day. Codd does not anticipate that he will have any further problems: “Although most patients with large prolactinomas need lifelong suppressive medication therapy, for those who can tolerate it well like this patient, the therapy usually has minimal impact on their life. And his vision has significantly improved in what seems to be a durable recovery.”